Taste for life, kindness, Pierre Soulages gets straight to the point: an interview becomes an encounter, with a storyteller’s talent and immense generosity. Because he believes in teaching through conversation. At 90, he is the greatest living French painter. A colorful encounter with this giant of black.

Interview by Christophe Mory

Christophe Mory: From October 14th until March 8th, the Centre Pompidou in Paris is celebrating you in a major retrospective; 2,500 m2, unheard of for a living painter. How are you experiencing this?

Pierre Soulages: It’s enormous, indeed. I prefer the term « ensemble exhibition » to the word retrospective. It’s better to look forward than backward. This exhibition is a unique moment. It’s not my first retrospective. The very first took place in 1967, I was 47 years old, at the National Museum of Modern Art. This made some people who were twenty years older than me, and still waiting, grind their teeth.

It appears that very early on you worked in Germany and the United States.

Was this a strategy on your part ?

There was Copenhagen, Munich, but it was mainly the Kootz gallery in New York that exhibited me and made me known in the fifties. First there was Sweeney, whom I didn’t know and who left me his card: « Curator of the MoMA in New York »… Previously, in France, from 1947, friends supported me: Fin and his brother Xavier Vilato (I would later learn that they were Picasso’s nephews), Francis Bott, Henri Goetz, Christine Boumeester (his wife), Roberta Gonzales (Hans Hartung’s wife). At the Salon des Surindépendants that year, Picabia, whom I didn’t know then, seeing the canvas I was exhibiting, said: « It’s the best in the Salon. » That’s what I was told. Later, when I met him, he asked me my age. « Twenty-seven years old. » Then he said: « I’m going to repeat what Pissarro told me… » I had before me someone who, with a whispered word, spanned Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, Dadaism, Surrealism to reach me. It was impressive.

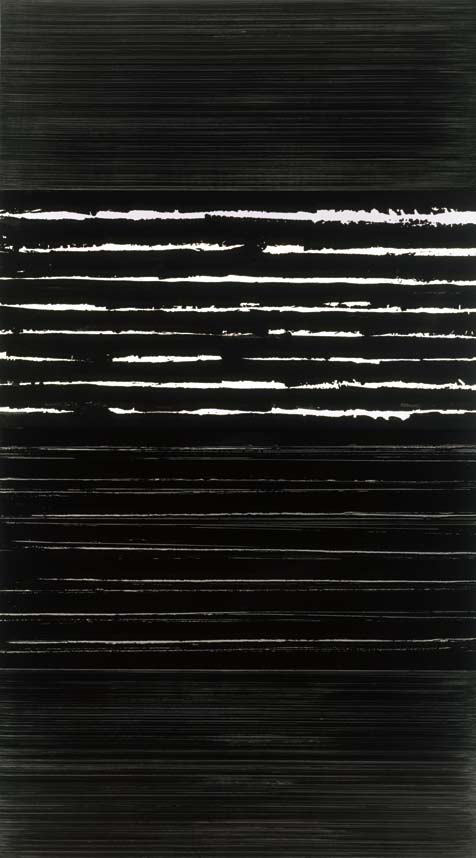

17 janvier 1970

Huile sur toile

Collection particulière

Paris, archives Pierre Soulages

Photo: François Walch

© Adagp, Paris 2009

And what was Pissarro’s word?

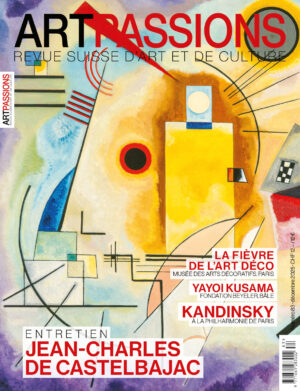

« With the age you have and with what you do, you will soon have many enemies. »

You’ve had many?

Friends first and enemies too, but « people who talk behind my back are talking to my ass » – a word from Picabia that puts things in perspective. You have to look ahead.

Reading about your career, one gets the impression of a fairy tale.

Events have followed one another despite myself. I’ve had a lot of luck, always and since my beginnings, which is as strange as it is abnormal.

You speak of the luck factor, but isn’t there first and foremost the work factor?

Certainly, but the luck factor dominates. The talent factor? I don’t know. I would rather speak of the originality factor. I came from another planet. Everything was red, yellow, blue; even Hartung was very colorful. And I arrived with black. At six years old, I painted in black and when I was asked what I wanted to represent, I said: « the snow. »

Your originality is compared to that of Rothko. What do you think?

It ends up annoying me, this story! If we’re talking about Mark because we were friends, let’s talk about Hans Hartung first… When Rothko came to Paris, we went to the Museum of Modern Art and there, he attentively looked at a port painted by Bonnard. I pointed out the reflection of a boat that I isolated by putting my fingers in a rectangle. They were three horizontal bands of different colors. Rothko looked and

said nothing. If we want to compare durations (it’s also an interesting angle) Rothko did Rothko, that is, magnificent canvases, for twenty years, after having done something other than Rothko for twenty-four years. I now have the chance of sixty years of painting. Our friendship was born of mutual sympathy.

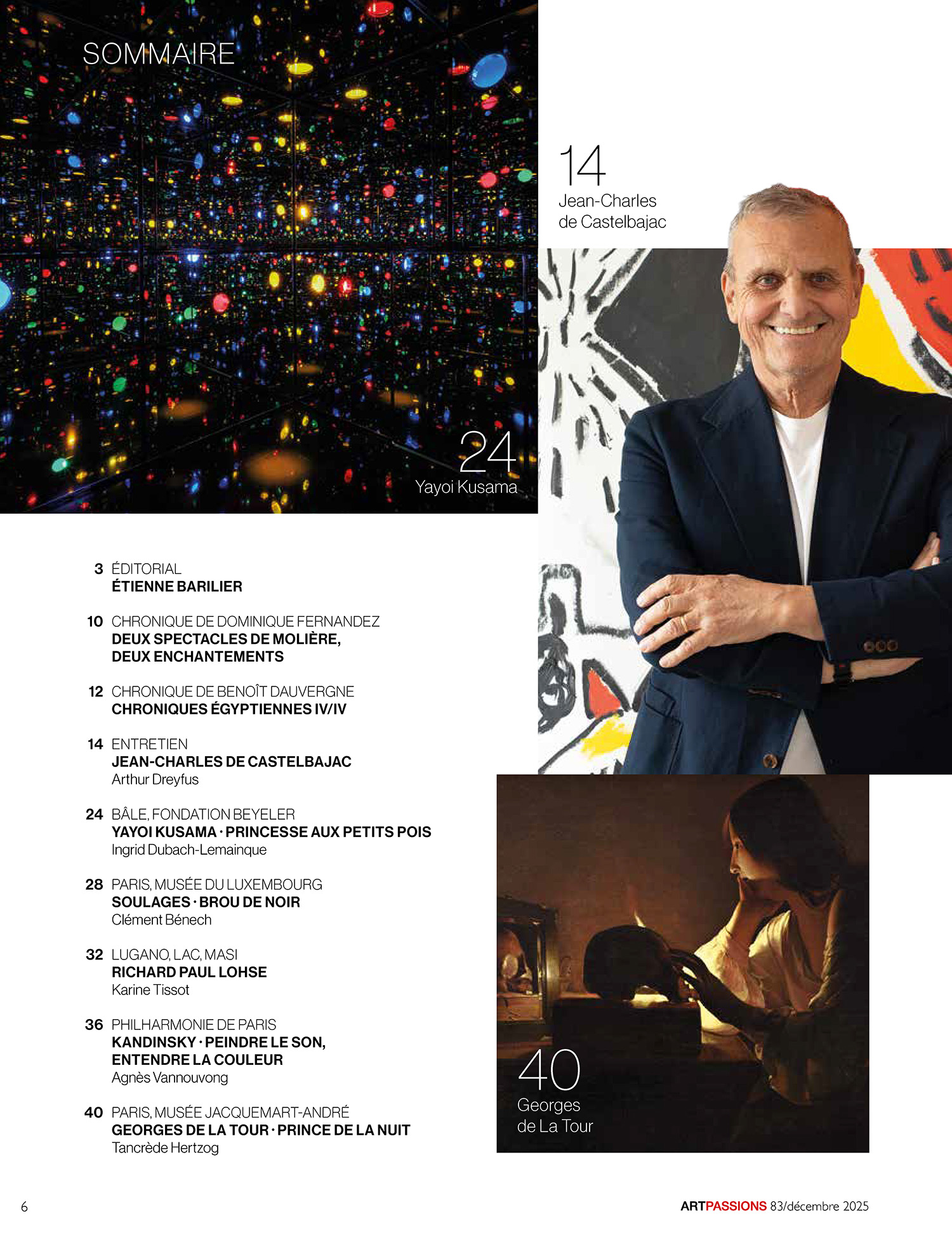

Isn’t this a convenient way to classify you…

I don’t like classifications. I was called abstract, which was not appropriate at the time. Non-figurative was worse! The term scandalized me: defining a painting or a movement by a negation is an enormity: art is something positive. They also wanted to place me among the concrete artists. But concrete is squares, circles, triangles; but these forms are figurative since they belong to geometry: the representation of

the concept is a figuration.

Is it to escape qualifications that you do not give titles to your paintings? Yet, it

is difficult to memorize a painting without a name. When we evoke Kandinsky

and « Improvisation X, » we immediately see what it is about. How can we talk

about one of your paintings without confusing it with others?

To memorize, you give a name but you refer the painting to something else and sometimes to what it is not. This is a very important problem and I have thought a lot about it. Everything comes from the word. When Victor Hugo paints a wave, it’s very beautiful. He titles it La Destinée (Destiny). It becomes a symbol. The word reverses everything. Take the example of Paul Klee. One day, I see a canvas that was not

what he had done best, and read the title: The Destroyed Labyrinth, 1939. The word illuminated the canvas. You will notice that I am not building a theory, I am basing myself on a personal experience and precise examples. Another example: I am in front of a Nicolas Poussin, a canvas that soothes me, that has a balance, that I enjoy seeing, a physical pleasure. The painting represents a landscape with characters

dressed as people then imagined the characters of the Bible. It is the story of Ruth and Boaz. You remember the verses of Victor Hugo: « While he slumbered, Ruth, a Moabitess, / Had lain down at the feet of Boaz, her breast bare. » The title of the painting gives a meaning but in this case, it completely distorts it. So, beware of words when you associate them with a thing.

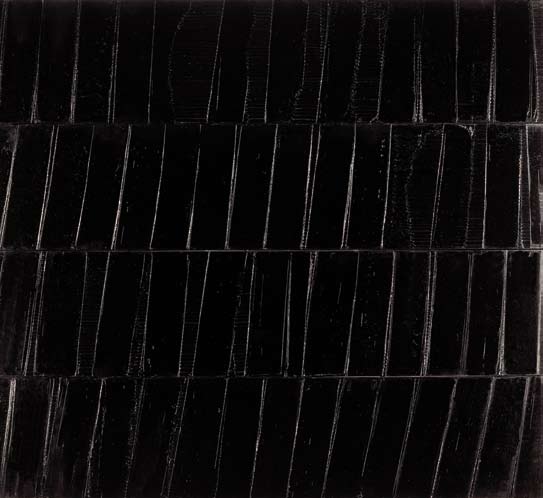

14 mars 1999

Acrylique/toile, polyptyque (4

éléments de 81 x 181 cm, superposés)

Collection particulière

Paris, archives Pierre Soulages

Photo: Jean-Louis Losi

© Adagp, Paris 2009

A thing ?

A canvas is a thing that is more complex than an object. I do not name it, I indicate its length, width and, in the past, its thickness. I describe its technical characteristics. A painting is a thing, for me, never a sign which refers to something other or elsewhere than the painting itself.

When does the thing become a work of art ?

The reality of a work comes from the triple relationship of the painter, the thing (that is, a set of forms, colors and their relations proposed to the spectator) and the spectator. Matter is not reality.

You say that art is a question of « mental field. »

It’s a convenient word and with which I get rid of many things.

Notably the question of the soul.

What is the soul? If we take the etymology, anima, it is the breath… I see no difference between the soul and the body. That’s why I’m embarrassed to talk about « soul » when I evoke the « mental field. » I am wary of shortcuts in this area. I am agnostic: I know that I do not know, although I find the message of Jesus Christ (« Love one another ») the best of all. I wonder, like everyone else, and end up distinguishing the sacred, the divine and the religious. The sacred is in all of us, even in those who do not know it. The divine? I have a doubt. The ideas we are given of God seem anthropomorphic, narrow, it’s embarrassing. The religious encompasses the two, sacred and divine: three things in one.

24 février 2008

Acrylique/toile, diptyque (2 éléments

de 222 x 157 cm, superposés)

Collection particulière

Paris, archives Pierre Soulages

Photo: Georges Poncet

© Adagp, Paris 2009

You may be a religious person who doesn’t know it ?

After what I have just said, I don’t think so. I am convinced of the sacred but everyone does not place it in the same place.

At ninety years old, are you afraid of death ?

I think it stops and that’s it. If there is nothing, you feel nothing. When you consider the Earth, the solar system, the sun a star in the billion of our galaxy, the Milky Way, the clusters of galaxies, the universe … We are not nothing, we are less than nothing. You created the stained glass windows of the Conques abbey church. Was this an experience of the sacred?

Conques is a personal story that can be summarized in four encounters. At twelve years old, a school visit led me there. There, seeing the proportions, the grandeur, the strength of this building combined with the grace and proportions of the nave, I decided that my life would be entirely devoted to painting, it’s what I loved to do. First encounter! In 1942, I married Colette. We spent our honeymoon in Conques: a marvel. Second encounter! My mother had taken me, as a child, to the abbey church to see the reliquary of Sainte Foy so venerated by pilgrims. This statue is frightening! I later wanted to show it to Pierrette Bloch and her friend Ludmilla Gagarine. On our arrival, the reliquary was removed; restorers had dismembered it to check the wooden statue buried under the gold plates. They asked me to reassemble it since I had said that I knew it well. I took the trunk. My hands were shaking. I was fifty years old and the fears of my childhood came back to me. I put everything back in place impeccably: the four balls, the crown… Third encounter! I am asked to create the 104 stained glass windows. I had made a stained glass window for a museum in Aachen, which was a kind of mosaic painting of glass slabs; I had refused other orders. Stained glass windows that are only paintings seen through transparency do not interest me.

Fourth encounter. In what state of mind were you?

I scrutinized the abbey church. It was made of light, for light. When you think that the bays of the North of the nave are smaller, lower, narrower than those of the South, it is inexplicable. The light was organized voluntarily. It had to be respected and enhanced. I placed myself in an objective observation. I took this monument as it had come to us, as we loved it, with what we were. I had three objectives: 1. That the gaze is not diverted to the outside – with a stained glass window that even with antique glass is more or less transparent, you can guess trees, roofs… The stained glass windows had to be opaque like alabaster, but alabaster was not suitable because of its yellowish color and its veins that would not correspond to the rather austere style of this place. 2. That the stained glass windows extend the walls, that they are not holes like windows are. 3. That the stained glass windows are emitters of light. When I said this to Georges Duby, he replied that I was looking for a « metaphysical light. » No, my goal was concrete: I started to measure everything. The light sought had to differentiate itself from the architecture to better serve it; to better give it to see in its singularity.

Polyptyque C (4 éléments

de 81 x 362 cm, superposés)

Huile sur toile

Collection Centre Pompidou,

Musée national d’art moderne

Diffusion RMN

© Adagp, Paris 2009

How do you envision it?

In this architecture, opacity and verticality dominate. But the world of light is a moving world, in motion, from morning to evening. Light and breath oppose opacity and heaviness. I chose oblique rhythms. I did not find the glass I wanted, neither in Germany nor in Italy. I made nearly eight hundred trials. In Marseille, a glassmaker told me: « If you continue, you will devitrify; it will not be glass, it will be like stone! » And I thought that if I could make the two states coexist together, I would have the modulation; the desired light in its translucency.

During these seven years of work, the clients must have been impatient ?

Everyone was waiting for me to present my projects. At a decisive meeting, I explained that I refused to make sketches with a pictorial process. I was looking for a light with materials that would serve to produce it. And I arrived with a large piece of glass. They accepted, I continued.

Huile sur toile

Collection Centre Pompidou,

Musée national d’art moderne

Diffusion RMN

© Adagp, Paris 2009

Were you so sure of the effects of your work ?

I had done a lot of tests at all hours of the day and in all seasons. Towards the end, I fitted a window. And there, astonishment: the totally colorless and translucent glass that I had created was colored. When the light passes, it is blue. When it passes less, we see a warm tone, rather orange. I went out and, my heart pounding, I believed in a catastrophe: the blue that was missing inside was outside. As there was no color other than that of the light, what I saw was the color of the light that this glass revealed and which was the one that the whole building received. Today, visitors come to study this phenomenon.

Do you have the impression that this success escapes you?

It has exceeded my intentions. I wanted to serve a place with a light. What matters to me is what is happening now. Before, this abbey church had 300,000 visitors per year and you could hear murmurs, people talking. Today, there are 500,000 visitors each year in almost absolute silence.

45,5 x 76,5 cm, 1948

Collection particulière

Paris, archives Pierre Soulages

© Adagp, Paris 2009

How are your days at the studio ?

When I arrive, I don’t know what I’m going to do. I look for a format, a canvas, I put it on the floor and I wait. I put it back on the wall. At that moment, I wait. I wait to dare.

And sometimes nothing happens.

Daring the gesture or the preparation ?

Daring to do something on it. Sometimes, I soil it a little and something begins to germinate. Sometimes, it doesn’t come. Or it starts, advances, continues and then it collapses along the way. Then, I turn the canvas against the wall and later, I take it back. If I realize that it works, I continue. Or, after a few days, I destroy it and burn it.

Do you work with music ?

Never! If you listen to something beautiful while working, you imagine that you are doing something beautiful. At the studio, I am all in what I do.

Do you feel the weight of solitude ?

I feel it and I seek it. For me, it’s not a weight but a precious and rare moment. I don’t like to be disturbed. I place a pebble in front of the studio door to prevent passage.

Do you work every day ?

At the studio? No. But painting inhabits me, and I only really think about it with the tools in hand.

In the materials you use, do you seek durability ?

Durability is in the spirit and the shock you received. It is in what you take away with you, which has shaken you to the depths of yourself. That is the true duration of a work; it remains in you, you can see it again and see it differently.

Should your canvases, or rather things, be framed ?

Absolutely not! The frame is the place where you are. I saw at the FIAC a thing framed with a very heavy, very old wood. I was scandalized, I told the dealer. It seems that it was individuals who committed this horror.

What is the ideal museum for you ?

The one where you can be alone with the work that touches you. It is the place where a little boy arrives and realizes that art deeply touches his life. What happened to me.

Is this what you want for the Rodez Museum ?

The mayor, intelligent, sympathetic and skillful, first asked me for the cartoons of the Conques stained glass windows that were sleeping in a corner of the studio. Then, he asked me for a copy of my engravings, then children’s and adolescent drawings. I saw the blow coming: « You are setting up the Soulages museum that I refused in Montpellier. » Finally, I accepted on the condition that there be 500 m2 of temporary exhibitions. So that we can also see a living art other than my works.

How to reproduce your things ?

A canvas, such as the Outrenoirs, is a specific thing that cannot be photographed, which does not support any medium. There is a uniqueness that cannot be found elsewhere. It took Hartung’s persuasion for me to accept that they be photographed from my beginnings. He told me: « If you don’t accept, it will turn against you. »

When we look at a canvas of yours, we wonder how much time you spent making it.

Sixty years.

What moves you…

…in an object ?

The perfect adaptation of the object to its purpose.

…in a painting ?

What, in it, dynamizes what inhabits me, or better yet, makes it born.

…in a sculpture ?

Same thing.

…in a photograph ?

It varies according to the photo: sometimes the unexpected, sometimes the light,

sometimes the meaning, the memories, the events, the people, the places, etc.

…in a book ?

Everything it sets in motion in me.

…in a music?

More often the rhythm than the melody.

If you had to choose a work…

…in painting?

Impossible choice.

…in sculpture?

Impossible choice.

…in music?

Impossible choice.

…in architecture?

The Abbey Church of Conques, of course, but not only.

…in literature?

Impossible choice.

In a few words

“It is what I do that teaches me what I am looking for”

Timeline

1919 | Born in Rodez, December 24.

1938 | « Goes up » to Paris to teach drawing. Enters the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-arts de Paris which he leaves, disappointed with the teaching.

1947 | Exhibits at the Salon des Indépendants (Paris).

1948 | One of his works is chosen to create the poster for the exhibition Französische abstrakte Malerei.

1949 | First personal exhibition at the Lydia Conti gallery in Paris.

1951 | First paintings acquired by American museums. (Currently, more than one hundred and fifty works are exhibited in museums around the world).

From 1949 to 1952 | Realization of three theater and ballet sets. First etchings.

1960 | First retrospectives in the museums of Hanover, Essen, Zurich and The Hague.

1967 | First retrospective at the National Museum of Modern Art (Paris).

1979 | Discovers "l'Outre-noir" (Beyond Black). Exhibition at the Centre Pompidou.

1987-1994 | Creates the stained glass windows of the Abbey Church of Sainte-Foy de Conques.

2008 | Sale at Sotheby’s in Paris of « Peinture, 21 juillet 1958 » sold for 1,500,000 euros, a record for a living French artist.

2009-2010 | Retrospective at the National Museum of Modern Art, Centre Pompidou, Paris. Event unanimously praised by critics and the public.

![[EN] Ernst Beyeler: The Lord of Basel](https://artpassions.ch/wp-content/smush-webp/2025/03/cc01-300x195.jpg.webp)