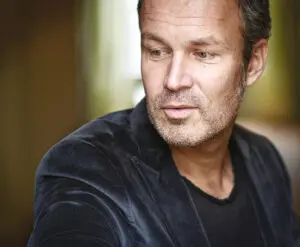

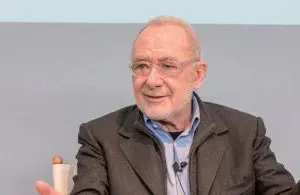

Interview by Robert Kopp

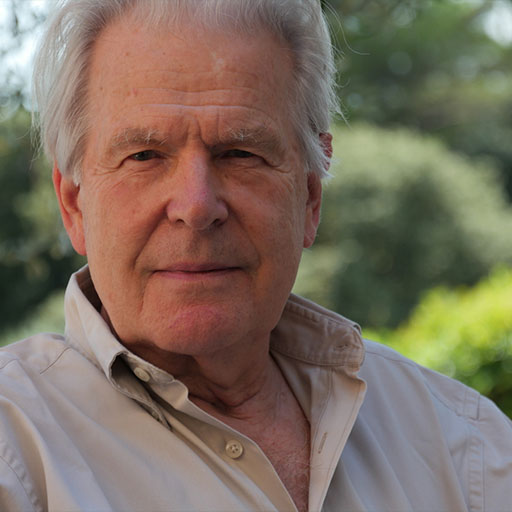

Poet, novelist, essayist – and also a painter – Jacques Chessex has, for over thirty years, dominated the literary landscape of French-speaking Switzerland from a great height. Even more: he has established himself as one of the most important writers, one of the most accomplished artists of our time. A classic, with all the ambiguity that word implies: he is admired more than he is read.

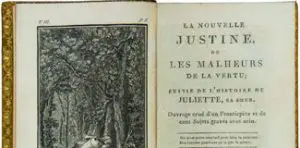

However, in the sixties, La Confession du pasteur Burg (The Confession of Pastor Burg) provoked the indignation of the self-righteous. At the time of the National Exhibition and in the midst of the Cold War, when it was so easy to distinguish between good and evil, Swiss conformism hardly accepted that the profane should be openly mixed with the sacred and that sex should be spoken of frankly in connection with religion. Chessex’s novel looked very much like a very large pebble thrown into the pond of a hypocritically dormant water. At that time, only Tinguely clamored through the clatter of his mad machines that everything was not running as smoothly as people wanted to believe.

A few years later, the Prix Goncourt – awarded for the first time to a French-speaking Swiss writer – crowned L’Ogre (The Ogre), another hard-hitting novel. New scandal. First, that of celebrity, drawing the sometimes embarrassed attention of the general public to an author whom Jean Paulhan and Marcel Arland had long welcomed to La NRF (Nouvelle Revue Française). Secondly, that of daring to turn his back on the New Novel, which then seemed to dictate the law, and of telling – in the manner of Balzac, Flaubert or Maupassant – a story, certainly unusual and in an acerbic language, of the kind that tears away the veils.

Robert Kopp: Jacques Chessex, what memory do you have today of this sensational entry onto the literary scene? Why so much sound and fury?

Jacques Chessex: It is difficult to imagine the intellectual and moral climate that reigned in Switzerland in the sixties to eighties. A heavy cloak of hypocrisy covered a whole series of carefully buried conflicts, many of which dated back to the Second World War.

Some of them have since erupted. Switzerland is not at all that picture-postcard country where an invariably blue sky extends over lakes and mountains. Switzerland has nothing of that Rousseauist idyll that our tourist offices successfully sell. Switzerland is a country riddled with deep violence; it is closer to the madhouse than the musical box. Except that the lid is firmly screwed on the pot, but the pot can explode at any moment. I am very sensitive to this swiss made madness; I feel it deep within me. In many of my books, I have tried to give it substance, because I hate nothing so much as hypocrisy, the implicit, the unspoken.

And that is how you gave free rein to what one might call a real hatred of Switzerland. You were not the only one, by the way, to feel it; Dürrenmatt and Frisch were not very tender with their country either.

You are right. But I didn’t only have scores to settle with Switzerland, I also had scores to settle with myself, with the death of my father and many other things. The outbursts of anger correspond to a specific period, which begins with La Confession du pasteur Burg and ends with Judas le transparent (Judas the Transparent). It will therefore have lasted about twenty years. Years, it is true, of violence, of excesses of all kinds: I went very far in the sense of self-destruction and at the same time, I was driven by a need for spirituality bordering on mysticism. I went from the most ardent faith to the denial of Peter.

In short, you were torn between the two simultaneous postulations of which Baudelaire speaks, one towards God, the other towards Satan, spirituality or the desire to rise in rank, animality or the joy of descending.

Indeed, I felt and still feel very close to Baudelaire and perhaps even more to Agrippa d’Aubigné, the great baroque poet of the Wars of Religion, from whom Baudelaire borrowed the epigraph placed at the head of Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil). I have always had a deep affinity with this poetry of excess, of exuberance, with this devastating lyricism that I tried to contain for a long time, but to which I finally gave free rein.

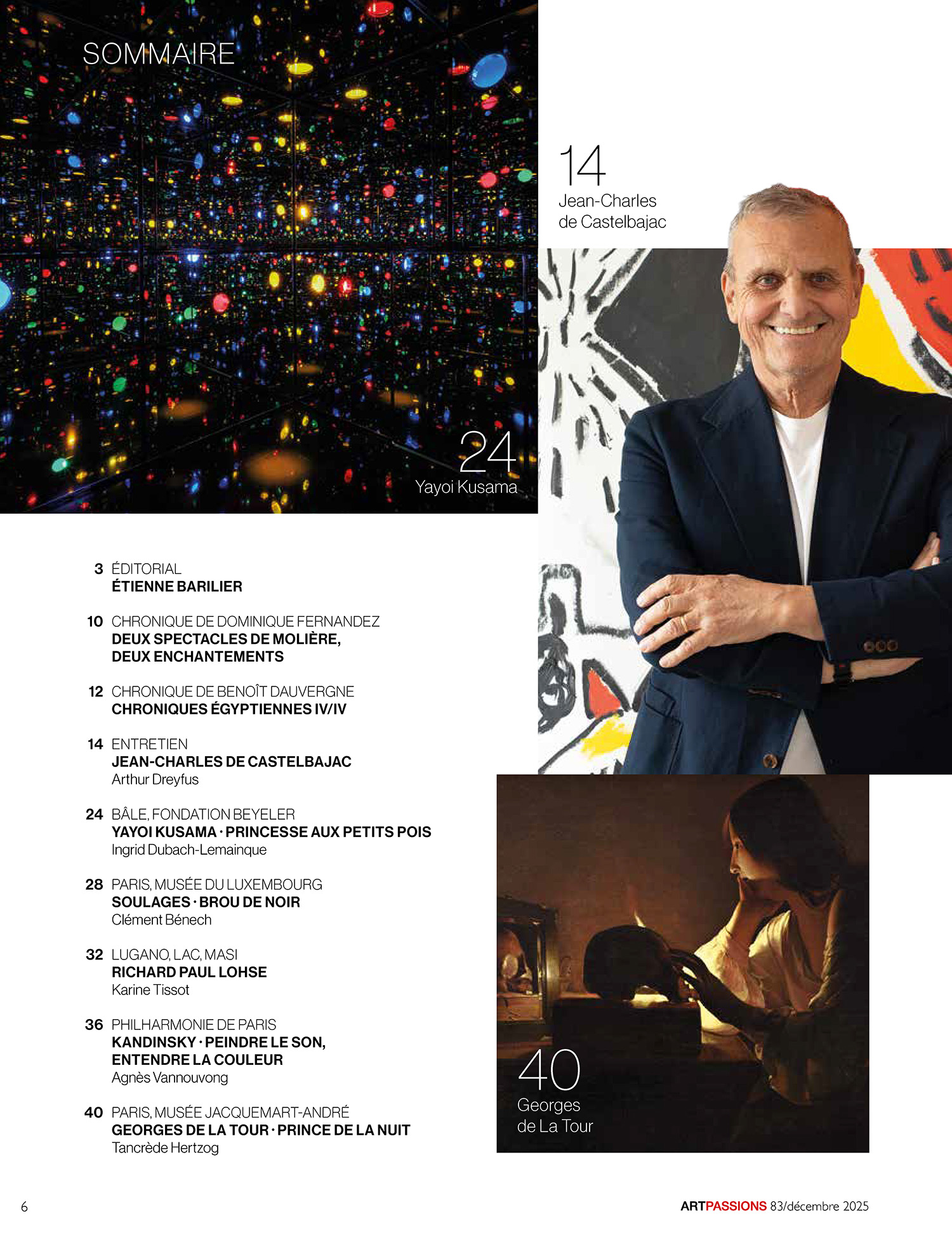

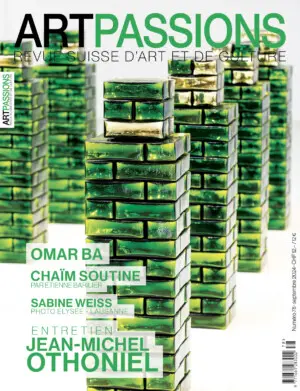

Mengele (Hoch-Altar), 1986

Bâle, Musée Tinguely

© 2009, ProLitteris, Zurich

Photo: Christian Baur, Bâle

This is quite the opposite of the Protestant restraint in which you were brought up and which characterizes your first collections of poems and your first contributions to La NRF.

Jean Paulhan and Marcel Arland, who welcomed me when I left my studies, when I was twenty-five years old, mistrusted lyricism. The spirit of La NRF was still that of Gide who said: « Classicism is a tamed romanticism ». They emphasized the word « tamed », and my first prose pieces, my first poems, are indeed very « measured », as are my chronicles on Queneau, Mandiargues, Calet, or my studies devoted to Gustave Roud, to Georges Peillex and others. It was also the time when I was immersed in L’Institution de la religion chrétienne (The Institutes of the Christian Religion) by Calvin. It must be remembered that Calvin is not only one of the founders of the reformed religion but also of classical French prose.

But at some point, it’s as if a dam broke. When Marcel Arland asks you for a text for the tribute issue that La NRF dedicates to Audiberti, just after his death in 1965, you send a great baroque poem on the theme « What has become of the dead Jacques? ». And, to your great astonishment, Arland accepts. You had become a « baroque Calvinist ». Isn’t that somewhat contradictory?

Not at all as far as I am concerned. I come from both Calvin and Ignatius of Loyola. I was born in Payerne, in an old Protestant family, especially on my mother’s side, originally from Vallorbe. They were people of austere rigor; I tried to bring them back to life in Portraits des Vaudois (Portraits of the Vaudois), a book that I wrote at the request of Bertil Galland who had asked me to make a counterpart to Maurice Chappaz’s Portrait des Valaisans (Portrait of the Valaisans). My father was a professor of history and Latin. A very erudite man and author of numerous books on the origin of proper names, on the history of Payerne, Avenches, Romainmôtier, Montreux. In 1943, he was appointed director of the Collège Scientifique Cantonal in Lausanne, where I myself taught later for many years.

But who introduced you to Loyola?

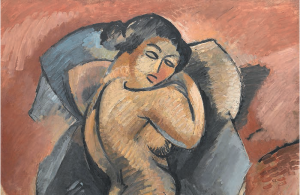

At 17, I wanted to leave school to enter the Fine Arts, because I hesitated between literature and painting. I loved Holbein, Goya, Courbet, Manet, Picasso and I drew and painted at the same time as I composed poems under the influence of Villon, Baudelaire, Verlaine….

It was your mother who pushed you towards literature?

That’s right. And she made me do my baccalaureate in Fribourg, at the Collège Saint-Michel. It was there that I had teachers of great quality – I am thinking of Father Pierre-Marie Emonet, Abbot Carrier, Abbot Dutoit – who initiated me into scholasticism, into the thought of Saint Thomas, of Saint Ignatius. I was very attracted by Catholicism…

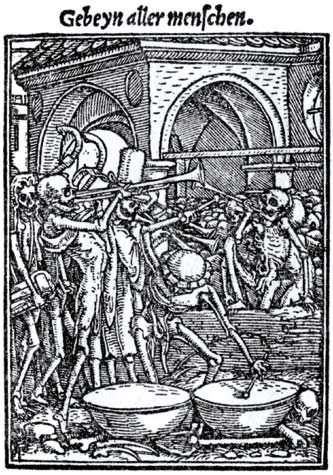

Hence your love of the baroque and your interest in the dance of death. I sometimes have the impression that all your work is not only deeply religious, but that it is placed under the sign of memento mori.

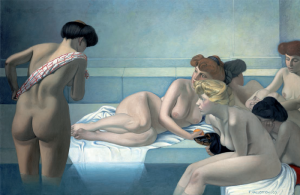

This vision pleases me quite a bit. It also explains my love for Jean Tinguely. I only met him relatively late. His work too – just think of his creations of Notre-Dame des Abattoirs in Fribourg – is of religious essence. Among his last great compositions, there is a whole series of triptychs celebrating, in an ironic way, the death of our civilization which, alas, is not followed by any resurrection in his work. At the end of his life, we had the idea of a book together, a tribute to Holbein’s Dance of Death; it was to be called Nouvelle danse des morts. Hommage à Holbein (New Dance of Death. Homage to Holbein). I was to write the texts that would alternate with his drawings. Unfortunately, he died before we could start working…

Many of your books were born from a collaboration with painters. You have also published numerous studies on the work of your painter friends. You seem to have a need for images. Another very un-Protestant attitude…

Poetry and painting have always been intimately linked for me. They unfold, each in its own way, in the space of the page; they maintain a logical relationship that puts things in place. My first collections of poetry, already, were thus the fruit of collaborations with painters: Une voix dans la nuit (A Voice in the Night), published in 1957, contains drawings by Jacques Berger, Batailles dans l’air (Battles in the Air), published two years later, drawings by Bazaine. Then came Pierre Estopey, Moira Cayetano, Cécile Mühlstein, Pietro Sarto, Marcel Mathys, Pierre Keller, Chantal Moret and many others.

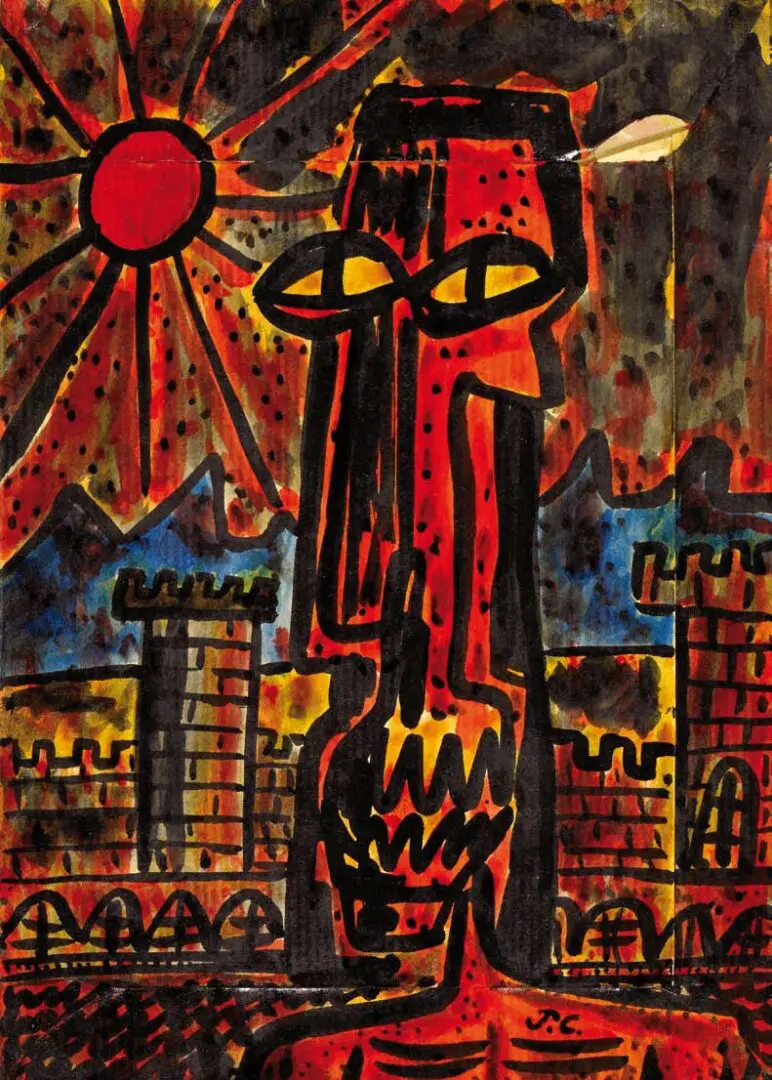

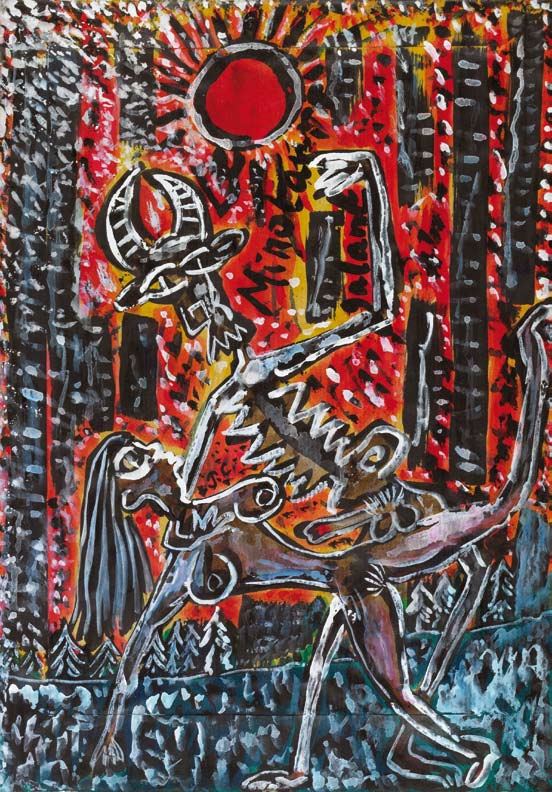

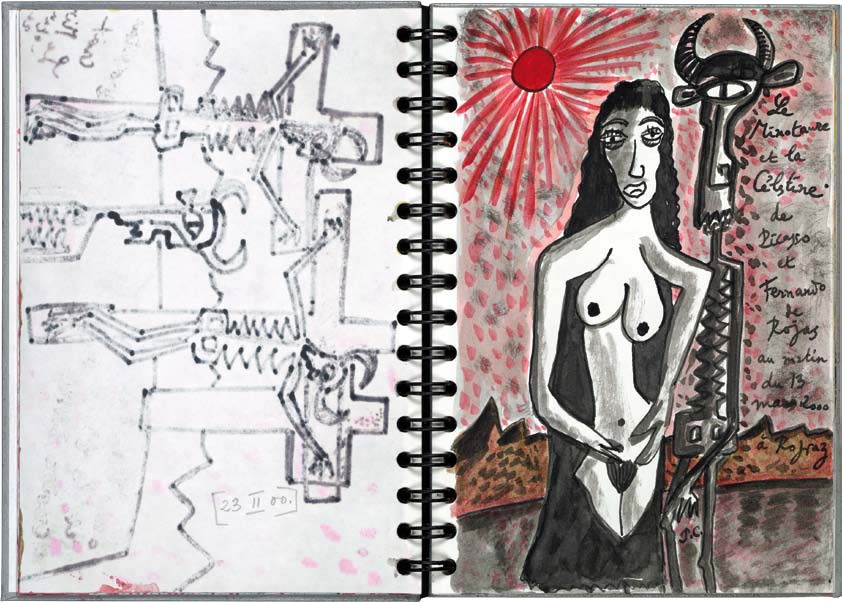

Not to mention your own paintings, such as the Carnets du Minotaure (Notebooks of the Minotaur). A tribute to Picasso?

Picasso is obviously present in the background. He totally dominates the painting of the 20th century. He absorbed everything, destroyed everything and recreated everything. But the Minotaur is also both a life force and a threat of death. It is Eros and Thanatos united in the same myth, it is love that can only be accomplished in death.

Let’s go back to your beginnings for a moment. Where was French-speaking Swiss literature in the fifties, when you decided to devote yourself to letters?

It was nowhere. Or more precisely, it was totally dominated by Charles-Ferdinand Ramuz, whose legacy no one dared to assume. The real legacy, I mean, which has nothing to do with the « winegrowers’ festival » spirit. The first to understand this was Jacques Mercanton, a great writer and a great European mind, too little known today and whose scope will be measured when his executors finally dare to publish the Journal, which has remained unpublished because it contains truths that could be hurtful.

So, for you, the problem of French-speaking Swiss literature, so often debated in the sixties, is a false problem.

Totally. It does not exist, only a French-speaking Swiss complex exists, made of pettiness and small-mindedness. It manifested itself between the two wars in the form of a detestable chauvinism, exalting order and tradition. It was against this spirit that Bertil Galland and I founded the magazine Écriture (Writing). Very quickly, we came into conflict with the Cahiers de la Renaissance vaudoise (Notebooks of the Vaud Renaissance) animated by Marcel Regamey. For Bertil Galland and for me, a French-speaking Swiss literature could only make sense if it came out of its borders.

How can we classify writers as different as Maurice Chappaz, Georges Borgeaud, Yves Velan or Philippe Monnier under the same banner?

I told you: French-speaking Swiss literature could exist in the time of Amiel, but not today. This does not prevent us from noting that French-speaking Swiss Protestant writers often have in common a certain sense of the concrete, a penchant for introspection, a kind of metaphysical unease, while a sense of the spiritual characterizes more the writers of Catholic origin.

Once again, one is tempted to say that you participate in both tendencies: your novels are both nourished by your life and traversed by the anguish of death, while many of your poems are closer to praise, as suggested by certain titles, such as Allegria.

Yes, my novels undeniably have an autobiographical character. But they are novels, even if I talk about my father, my mother, my relationships with them. Other books are stories based on observations, memories of specific facts.

Like this story that you witnessed in 1942, at the age of eight, and that you are only able to tell now: Un Juif pour l’exemple (A Jew for Example)?

That’s not quite right. I have spoken several times about this atrocious story, for example in a short text, « Un crime en 1942 » (A Crime in 1942), but without telling it in detail, without going to the bottom of it, which is what I have tried to do now in Un Juif pour l’exemple. I have been haunted by it all my life; but for a story to become a book, it sometimes takes a long maturation for me to grasp what I would call « my ideal part ». In this specific case, I had to be able to finally redeem my guilt. Because I have always asked myself « why him, why not me? » Then, I wrote the book very quickly, in a month and a half, and I read it as I went along to Sandrine, because I need the « gueuloir » (den), like Flaubert.

Does this anti-Semitism that you witnessed at the time of the Second World War still exist?

It still exists in a more or less latent state, and not only in Payerne. The history of Switzerland in the 20th century remains to be written, the history of mentalities, I mean; the influence that movements like « Order and Tradition » had has not been brought to light, hence this oppressive climate of the sixties to eighties that we have talked about. The return of the repressed is far from complete. The violent reactions that my book has provoked prove it. The author was burned in effigy on the very site of the crime. But I remain very calm in the face of these ignoble attacks (it is a trait that I inherited from my mother). My answer will be the film based on the book which, I hope, will make an even wider audience aware of this atrocious crime.

Un Juif pour l’exemple is not the only book whose material is a story that you have lived through. Through more than one fictional character, one has the impression of guessing the silhouette of your father, of your mother. It is your life that you are telling, in the end.

Yes and no. L’Ogre is a novel, as is L’Ardent Royaume (The Ardent Kingdom) or Les Yeux jaunes (The Yellow Eyes). They are nourished by my experience, certainly, but they are fictions that obey the laws of works of fiction. Of course, when I write Monsieur or Pardon mère (Forgive me Mother), I am talking about myself. But it would be a mistake to read my novels only in the light of my autobiographical writings…. After all, an author always talks about himself, even indirectly. When you talk about the writers you love – Gustave Roud, Ramuz, Maurice Chappaz, Philippe Jaccottet – it’s still you. The same is true for painters.

Of course. Paying tribute to a predecessor, to a friend, is saying that one feels in communion with his work, that one recognizes oneself in it, that, in the night that surrounds us, we recognize voices similar to our own.

Nota Bene

Find paintings by Jacques Chessex at Sandrine Fontaine Fine Art Courtage Av. des Alpes 5, Lausanne www.sandrine-fontaine.ch

Jacques Chessex peintures Editions de la matze 136 pages

In a Few Words

What moves you…

…in an object?

Its magical intensity

…in a painting?

Its power to radiate within me, which awakens me to other paintings

…in a sculpture?

The wild power of its plastic eroticism

…in a photograph?

Its resemblance to the imaginary portrait, the one I could have made myself of its model. But I am not a photographer.

…in a book?

Its lasting resemblance to my own figure

…in music?

Its rhythm

…in architecture?

Its incandescent nudity

If you had to choose a work…

…in painting?

I would like to choose several: the disfigurements of Antonio Saura, the cruel series of Francis Bacon, the entire work of André Masson. In current Switzerland: all the painting of Jean Lecoultre.

…in sculpture?

Without a doubt Alberto Giacometti. In current Switzerland: Manuel Müller

…in music?

Bach, Mozart, Schubert and in contemporary music the blues of New Orleans and Miles Davis.

…in architecture?

What I prefer in architecture are baroque churches: the Saint-Ours cathedral in Solothurn, Saint-Canisius in Fribourg, Sainte-Marie-Madeleine in Aix-en-Provence.

…in literature?

The entire works of Flaubert

Trajectory

Born in Payerne in 1934 | Prix Goncourt in 1973 | Grand Prix Jean Giono in 2007 for his entire body of work | Knight of the Legion of Honor; Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters | Member of the jury of the Prix Médicis in Paris