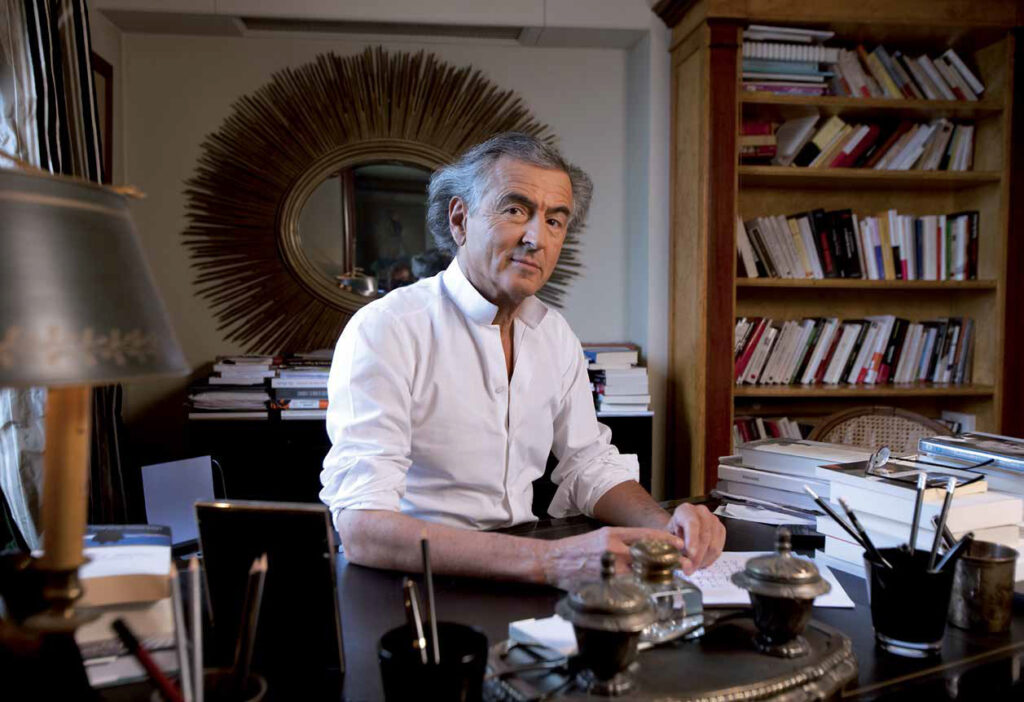

Interview by Tancrède Hertzog

An intellectual deeply involved in current affairs, you are completely changing your focus with an exhibition this summer at the Maeght Foundation in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, on the relationship between philosophy and painting, from Plato to the present day. Is this a rest for the warrior, a complete change of pace, an excursion into the enchanted world of the arts? Or is it a return to philosophy through painting?

Bernard-Henri Lévy: A return, obviously, to philosophy. Or rather, a kind of rendezvous, secretly planned for a long time, between the philosopher that I am and the question of Art. Barbarie à visage humain (Barbarism with a Human Face) concluded with the idea that art – I said at the time, the novel – is the only tool of thought capable of addressing the most burning metaphysical questions, the most insoluble political questions, and, in particular, the need to look Evil in the face. Since then, I’ve had in mind that one day or another I would have to confront these questions. Here we are, it seems.

No one has really attempted this exploration. Isn’t it a gamble to confront two thousand years of art history and the history of philosophy, to put them face to face?

I’m not sure that no one has attempted the adventure. There have been works here and there. Some young philosophers (Élie During… Donatien Grau…) have reflected on these questions. What I have tried to do is to take the matter head-on, and comprehensively. The idea of confronting these two histories, of crossing them, may seem absurd. And no doubt it took all my recklessness, all my profane amateurism. But I did it joyfully, with enthusiasm.

The philosophy-painting relationship is not obvious: do they deal with aesthetics, with representation? Philosophers are not artists, and painters are even less philosophers. Two worlds that, globally, ignore each other, don’t they? Is there a common thread, a dialogue? What connects them? Do artists do philosophy like Monsieur Jourdain did prose?

Why like Monsieur Jourdain? They do philosophy. Their business – these are the first words of the letter to Olivier Kaeppelin that opens the book-catalog – is the business of truth. That being said, the relationship varies, of course, according to the times. But philosophers have abundantly concerned themselves with art and painting. Plato to discredit them, Kant and Schelling to celebrate them. And many painters, for their part, have been inhabited by philosophical questioning. We cannot say, therefore, that the two have ignored each other. And then, I insist, the common thread of the exhibition is not the question of representation, let alone that of beauty, but that of truth. Just as Aristotle said of Being that it is said in several senses, so too the question of truth is said in several languages. There is the language of philosophy. And there is, just as much, the language of painting, which is another mode of access, a path in itself, to this question of truth. What interested me in the exhibition was to make the two languages resonate, to make them speak together, to translate them into each other, to identify their areas of untranslatability or, on the contrary, of good consonance. It is this question of truth that is at the point of contact between the two.

à Michiel Cocxie

La Caverne de Platon

Huile sur bois 131 x 174 cm

Collection musée de

la Chartreuse de Douai

© Photo: Daniel Lefebvre

Another guiding thread recurs throughout your book-catalog as well as the exhibition itself: the question of iconoclasm.

There are two things. First, therefore, this confrontation, this war for the control of truth, this question of knowing who will seize this subject, who will be the best philalethe, the best lover, the best seeker of the gold of truth? And then there is, next, the question of iconoclasm which is something else entirely and which constitutes another guiding thread, more or less linked to the first, but which separates from it. It is the question of the prohibition placed on the image. This prohibition is uttered, originally, by philosophers and theologians to whom the image makers, and first of all the painters, had to face. Do they accept the prohibition? Do they refuse it? If they refuse it, how do they circumvent it? Worse, do they internalize it? Is it a version of the eternal history of voluntary servitude dear to La Boétie, an ukase to which the artists have submitted more or less voluntarily? The question of iconoclasm is a huge story. It is consubstantial with the history of the West, it structures it from beginning to end. It is a question from which the West, to this day, has never gotten rid of. It haunts the work of painters. It plagues them. Do they have the right to do what they do, to make painted forms? That is the question.

In this regard, you demonstrate that Jewish iconoclasm is a myth…

Yes. And an anti-Semitic myth. Or, more precisely, one that has fueled anti-Semitism. Judaism is after the idol, not after the icon. It is after the superstition of the image, not after the love of the image. Living Jewish thought (that is, not the Bible but the Talmud) has never prohibited painting! I take up, in the book, important texts from the midrashic commentary which clearly say that the question of the image, of the icon, has never been a question for Judaism. What is questionable is when men imagine that the image is God, that it is full of God or, worse, of gods in the plural. No, say the Jews. Nothing is God; God is not incarnated; no more in a man than in an image. When, before the image, man abdicates his intelligence, that is what Judaism is after; not after the image.

Painting-philosophy: you identify seven stations, seven temporalities equivalent to seven different postulates. One of them is the Nietzsche moment and the Counter-Being…

This is the decisive moment when a German philosopher says that everything must change, the terrain of thought must change. Philosophy, he tells us, has been boring us for twenty-four centuries with questions that have had the effect of producing a life at a discount, a tiny, degenerate life, a hatred of life and a hatred of the world. Nietzsche says that it is all the questions of philosophy that must be discarded, starting with the question of Being as it has been posed by philosophers and, consequently, discarding Being itself as it has been named and deployed. It is necessary, yes, to get rid of all that, to situate oneself elsewhere. The famous Nietzschean dancing of life relates much more, as we know, to music than to painting. But it can also be understood on the side of an activity which, by nature, has the power to break with philosophical questions, to situate itself elsewhere, and, for me, it is the activity of painters.

Sainte Véronique, École flamande,

XVe siècle, huile sur panneau

de bois 30,5 x 17,5 cm

Musée du monastère royal de

Brou, Bourg-en-Bresse

© Photo Philippe Hervouet, Musée de Brou

Then comes the shock of modern painting, with abstraction, then conceptual art, Kandinsky and Duchamp. Did they hear Nietzsche’s lesson, or, as you write, through them does Plato take his revenge?

There are two scenarios. The great abstract artists, such as Fontana but also Pollock and his drippings, Rothko or Barnett Newman, the great Russians such as Malevich, heard Nietzsche’s lesson. They took so seriously the idea that the question of Being is of no interest, that they install, pose the stilts, erect the theater of what I call another Being: a world that is no longer the copy, nor the continuation, nor the resurrection, nor even the metamorphosis of this world, but which is another world. They understand the Nietzschean lesson. On the other hand, another turning point, inaugurated by Marcel Duchamp, is that of conceptual art where traditional philosophy, its questions, return through the window, while we thought they had left through the door. Philosophical questioning regains power in the heads of contemporary artists, whom we thought had gotten rid of it.

The first of the seven sections of your adventure of truth deals with the Platonic ban, which strikes painting with anathema, as mimesis, resemblance to reality would be a lie. Philosophy, in its beginnings, is iconoclastic. Just like religion, especially Christianity (you cite, in the High Middle Ages, the bishops Serenus and Claude of Turin burning images). Then, facing the iconoclasts, second section: the painters invent a subterfuge, the veil of Veronica.

It is not a subterfuge but a stroke of crypto-evangelical genius which consists in saying, throughout the first millennium of the Christian era: you think that the image is the work of the demon, that it is a simulacrum and a pure semblance? Well, see this: the face of Christ making an image on a cloth, thanks to a young Jew present at the sixth station of the climb to Calvary. It is an apocryphal story, absent from the Gospels, invented from scratch by the iconophiles, artists and theologians together, for the teaching of religion through images, because the peoples to be evangelized cannot read the holy texts. And the painters began to paint cloths of this kind in chain! They started the image turbine, the mass media of the time. To prove what? Nothing less than the eminent dignity, the possible holiness of the image. If the image can really be that, if that can really be an image, if the face of Christ could really become an image, then the old Platonic prohibition taken up by Neoplatonism present in Catholic theology until very late, no longer had reason to be. There is image and image. There is the bad image, yes, on which the prohibition can continue to weigh; and there is the good image, that of which the series of Véronique in the exhibition testifies.

But, after the triumph of images in the classical age, art, says Hegel, for lack of seriousness, of patience specific to the work of the negative, is decreed by him, at the beginning of the 19th century, a « thing of the past »? Are there, before the Nietzschean painters, Hegelian painters?

For Hegel, there are no Hegelian painters since the triumph of spirit and reason in History, in the form of the accomplished State, signals the end of philosophy and, before the end of philosophy, the end of art. Art is a thing of the past, philosophy will soon be a thing of the past in its turn; there remains the epiphanic installation of absolute knowledge. For Hegel, it is not a question: painting is finished. But philosophers continue to do philosophy after Hegel. It is even the whole question of philosophy after Hegel: how to continue doing philosophy after the master of Jena? It is the question of Bataille, it is the question of Bergson, of Kierkegaard, of Wittgenstein, of Deleuze, of Nietzsche, of Heidegger. It is even the question of Sartre, the Critique of Dialectical Reason being nothing other than an enterprise where it is a matter of knowing whether Hegel is right or not – and, if not, how to prove it, how to prove him wrong, how not to ratify the Hegelian diagnosis. The same thing happens with the painters. A certain number admit that the Hegelian diagnosis is the right one, that the time of dialectic is over, and wonder what painting can look like, how to continue painting, after Hegel. A Hegelian painter is someone who wonders how to continue painting naked women, or still lifes, or saints, after the philosopher of the end of History and the end of philosophy. And then you have Chenavard, or Louis Janmot, these painters from the Lyon school, who say: « After all, it may be up to us, painters, to be responsible for Absolute Knowledge, to be its apostles. » And this gives a canvas baptized La Palingénésie sociale, pictorial version, inscription on the canvas and deployment of absolute knowledge. Such is the crazy dream of Chenavard, who thought he was the last painter. After him, painting would no longer have a reason to be!

(oeuvre créée spécialement pour

l’exposition), huile, émulsion,

acrylique, gomme laque, charbon,

sel et métal sur toile 190 x 380 cm

Courtesy Galerie Thaddeus Ropac,

Paris/Salzburg

© Anselm Kiefer – Photo: Charles Duprat

What is the Royal Road, this third moment in the history of painting?

This is the moment when painters become the heroes of this work of truth. We are coming out of a long period where painters were already happy to have a place in the sun, to have the right to work for the advent of truth. Philosophy, that is to say theology, was the queen science, but in the temple of truth, the painters were granted a modest folding seat. Comes, much more interesting, the moment when the painters say to themselves: basically, if it is to illustrate a sovereign knowledge that the philosophers have forged by their own means, if it is just to serve it and say it differently, it is not worth it. Art is only worthwhile if it is capable of producing unprecedented knowledge, new knowledge which, without it, would not be produced. This is the moment when painting realizes that it is capable of seeing in things, in the world, a background, a secret structure that had escaped the philosophers.

Who are these painters who see beyond the world described by philosophy?

These are, for example, the Cubists when, contrary to the Cartesian conception of the world based on the idea of an extension, of a simple materiality, they propose to decompose, fragment, dissolve, reassemble bodies, in a kind of science of bodies whose painting lovers realize that it enriches humanity.

The 20th century will see, you say, the face-to-face, warlike or complicit, of painting and philosophy. You speak of the merry-go-round of the plastemes of the philosophers and the philosophèmes of the painters. Do they exchange roles to this point?

Plastèmes and philosophèmes are statements that are said in both languages, painting and philosophy. I am powerfully interested, in the history of painting and in the history of philosophy, in the moment when one is at work in the other, the moment when one is the starter of the other. I am passionate when I see Michel Foucault working on the history of the Great Confinement, of prisons, of punishment in the classical age and then in the 19th century – and when I see that a painter makes him advance, allows him to advance, on the path of a new truth as much as a philosopher or a historian. This painter is called Rebeyrolle. In the text about him, « La force de fuir » (The Force to Flee), published two years before Surveiller et Punir (Discipline and Punish), Foucault does not simply repeat about him, and with him, what he has said elsewhere: Rebeyrolle makes him think a little more than what he thought, a little better than what he thought. Conversely, there are painters to whom philosophy allows them to go further, to move forward, including within their own philosophy. When Klossowski officially renounces philosophy, he amputates himself, he removes the nerve of philosophy, and he paints the Great Confinement, where we can see how philosophy is at work to make great painting. So, plastèmes and philosophèmes means that I am interested in that moment, when for some and for others, painting and philosophy both function as reciprocal starters of truth.

La Cène, XVIIe siècle

Huile sur toile, 182 x 266 cm

Musée des beaux-arts de Lyon

© Lyon MBA – Cliché Alain Basset

You declare that today, « artists must be liberated. » Liberated, as Nietzsche had wished in his time, from philosophy?

There was a moment, I said, when painting committed hara-kiri, renounced its right of citizenship that it had conquered with great difficulty, surrendering its arms to philosophy which was not asking for so much: the philosophers did not ask this of the artists, who did it anyway. This was the temptation of the monochrome, and it will be, similarly, closer to us, the temptation of conceptual art, the temptation of an art where the hand would play only an accessory role and where the brain would do everything. I see in it a kind of hidden, unconscious return to a form of modern iconoclasm…

« Liberate the artists. » But to go where, towards what? A return to a purely aesthetic, « gratuitous » conception of the work of art?

A return to the pleasure of painting, of inventing the world, of inventing a new world, of offering humanity unprecedented hypotheses about its condition. That belongs to the painters.

How exactly was the exhibition built? How did you proceed for the selection of the works? What was the criterion? Is it not yourself who decrees the meaning and the place that a work occupies in this secular duo between philosophy and painting?

This is always the risk in this kind of exhibition. In recent years, this has provoked controversies, protests from artists and not the least. We remember Buren’s controversy with the great curator Harald Szeemann, Buren protesting against the fact that his works, his installations, would be like words in the sentence of another and that Szeemann, as great exhibition curator as he was, claimed, took himself squarely for an artist himself, an artist in the second degree. It’s a real risk. This is not my case. I do not take myself, in this exhibition, for an artist. On the other hand, yes, I tell a story whose sequences are made up of paintings, I make a film, the most beautiful film in the world, because the scenes here are works of art. This temptation to substitute oneself for the works or to make them signify one’s own views exists, but unlike others I know it, I measure the pitfalls and I claim to have, for the most part, overcome them.

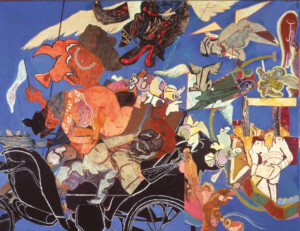

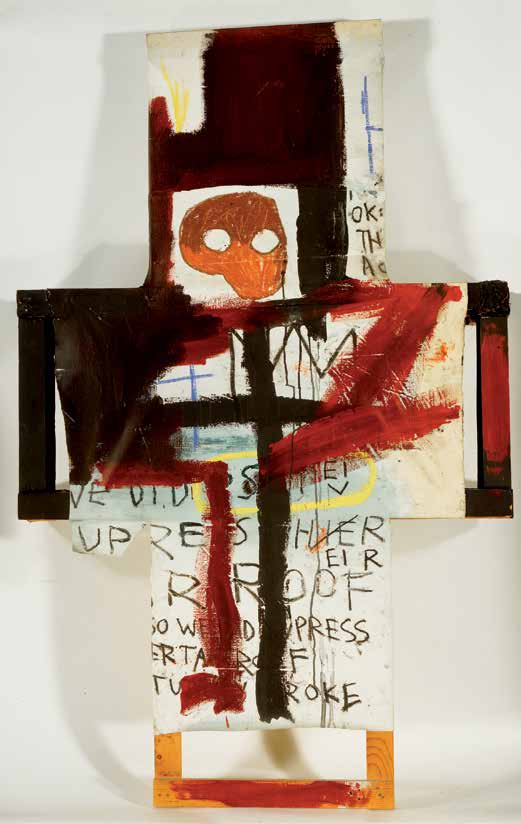

Crisis X, 1982.

Huile, acrylique et crayon gras sur

toile montée sur palette en bois,

185 x 115 x 17,5 cm

Succession Jan Krugier

© Succession Jan Krugier – the estate of

Jean-Michel Basquiat / Adagp, Paris 2013.

What do you do with the autonomy of art, its irreducibility to a final meaning, or even, in some artists, the displayed rejection of the « burden of meaning »?

I do not believe that art is irreducible to meaning. Art is twofold. By one end, it escapes meaning, and by another it submits to it. It is still not the painters, inventors of the art of collage, who will prevent philosophers from practicing collage in their turn and in their own way, that is to say, inscribing them in a story, a phenomenology, an Iliad and an Odyssey that are those of the spirit.

Contrary to Malraux’s Imaginary Museum, you intend in this exhibition to do the work of a philosopher and of knowledge. You are neither a curator nor an art historian. To embrace everything, it takes an almost infinite knowledge… Aren’t you afraid of the saying « grasp all, lose all »?

My museum, in fact, is not an imaginary museum like that of Malraux. It is even its opposite, since it is a concrete museum. Despite everything, grasp all, lose all? Perhaps, it is obviously always the risk of an undertaking like this, I do not have the impression, but it may be the risk.

You have explored museums, cleared collections, in France, in Europe, elsewhere. What were the great moments of the adventure, your discoveries? Your regrets, your disappointments too…

I think about it, but no, there are no regrets, there were no disappointments.

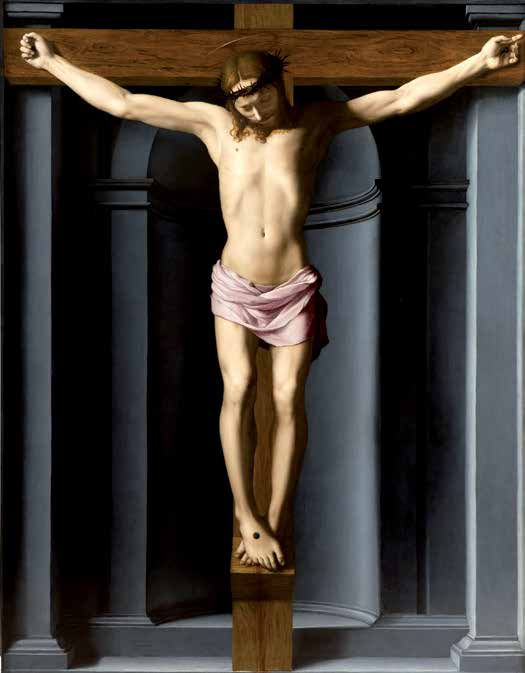

Crucifixion, c. 1540

Huile sur panneau

de bois, 145 x 115 cm

Collection Musée

des Beaux-Arts de Nice

© Ville de Nice, photo Muriel Anssens

Because, in this exhibition, one work is interchangeable with another?

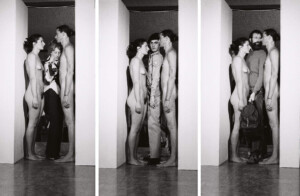

No, simply because all the works I intensely desired, I had them. I started from an exhibition project for which it would have taken five times the Maeght Foundation, and I reduced the number of works accordingly. But all the works on which I stopped, those that I desired, I obtained them. There were several great moments. First, there were these artists I knew and whose work I discovered that I was unaware of. Thus Le Grand renfermement (The Great Confinement) by Klossowski or the Pietà by Cosmè Tura, a painter I knew via Antonin Artaud, who defended this Renaissance artist very powerfully. I had probably seen this painting in Venice, during my first trip to Italy. Finding it again was an immense moment of emotion, of reunion with my youth. After that, there are artists I barely knew, for example Ryan Mendoza and Yang Jiechang, both present through videos, since, in parallel to the works exhibited, a room of the Foundation will be reserved for videos of about twenty contemporary artists reading a text of philosophy, by Spinoza, Kant, Aristotle or Montaigne, in connection with their work. I did not know well the work of the Chapman brothers, whose exhibition I had seen at the Sea Customs of the Pinault Foundation in Venice, a few years ago. There are artists whom I thought I knew and whom I discovered under a completely unexpected face, Marina Abramovic with her own version of Marcel Jean’s Spectre de Gardénia.

Are there works that, when you saw them in a museum, at a collector’s, an artist’s, in a gallery, proved essential for your exhibition? The shock of the encounter…

This is the case of Abramovic’s Communicator, the Chapman brothers’ Hellscape, which was not yet finished when I saw it in their London studio, but also of Bronzino’s sublime Crucifixion from the Nice museum, rediscovered in 2005 and whose existence I did not know. This is also the case of a work that I did not think of, which is La Cène (The Last Supper) by Philippe de Champaigne, at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Lyon. I discovered it when I went to this museum to convince the curators to lend me two works by Chenavard and Janmot. I came across this magnificent Cène, which Pascal may have seen when he came to visit his sister, a nun at Port-Royal de Paris, where the work was hung in the church.

You confront ancient, modern, and contemporary works in the rooms. Four Crucifixions are exhibited side by side, that of Bronzino, dated 1540, of Pollock, Basquiat and, finally, that of Cattelan of 2007. What does such a confrontation in time teach us?

It is the question of the crucifixion as an infinite, open question. What is crucified? Is it the body, is it the corpse? Is it the soul? Is it a divinized body? Is it, on the contrary, animalized? Why shouldn’t it be a woman, as in Maurizio Cattelan’s version, in a kind of extreme opening of the question? That is what this juxtaposition of the four Crucifixions teaches.

In the diary of the making-of of this exhibition, included in your book-catalog, you relate your meetings with great collectors. Scholars? Benefactors of humanity? Megalomaniacs, great madmen?

There are not « the » collectors, there are several kinds and in particular the sharing between the friends of life and the friends of death. Those who collect the works to make them live, and those who collect them to make them die. In some collectors, one has a physical feeling of the mortality of the works when one visits their house, their den, something morbid. Then there are collectors who we feel are collecting works, on the contrary, to make them live, to endow them with an added vitality, by subjecting them to ever new confrontations, by circulating them, by lending them, by grafting them onto different ensembles. The real sharing between collectors is there.

Without the vademecum that is your book, can the layman grasp, by the sole spectacle of the works, their meaning, their philosophical scope, their connection to such thought or to such a moment in the history of ideas?

You need the book or, failing that, a document that will be distributed to visitors to the exhibition. It is a philosopher’s exhibition. It is supported by the presence of the works and a discourse. You need both.

The art world awaits the event with great curiosity. It should be « the exhibition of the summer. » An outsider in the private domain of museologists and specialists in the art world. What reception do you hope for?

I do not ask myself the question. There too, the meeting with this milieu was part of this two-year journey that I retraced in my Journal: art historians, curators, these are friends of life and art. Here is an extraordinary devotion. These are people I respect infinitely. They will think what they want of this exhibition. It is up to them to seize it, to discuss it, to appreciate it, to depreciate it, it is their business.

Do you think you have invented a new type of curating, philosophical curating? The works as marks on the chessboard of historico-philosophical demonstration?

No, this connection of the works begins and ends with me, it is personal to me. This exhibition is a kind of fiction, it’s like a novel of which I would be the author, and there is no method, no discourse of the method, it resembles nothing known, there is not much to do with it, except to receive it as such.

This exhibition is nevertheless more a demonstration than a peregrination in your ideal museum. It has a structure, theses, a didactic optic; it includes a theoretical discourse, exposed in the book-catalog…

Yes, but each book of philosophy is different. Is there a genre of philosophy book? I do not believe in genre, the works are all unique. This exhibition is a completely unique work and I do not see who could be inspired by it.

You are a philosopher, and you deal with painting. Would you have liked to be a painter?

Yes, which means that I would have liked to live a century and a half earlier, because there was a time when philosophers and writers drew, painted: Hugo, Baudelaire, Mérimée, so many others.

What moves you…

…in an object?

Its uselessness.

…in a painting?

Its intelligence.

…in a sculpture?

Its absence.

…in a music?

I do not listen to it.

…in an architecture?

Its quarrel with nature.

…in a book?

Its polysemy.

If you had to choose a work…

…in painting?

Depends on the days.

…in sculpture?

The Triumph of Philosophy that Jacques Martinez has specially made for the exhibition.

…in music?

Same answer: I do not listen to it.

…in architecture?

A house by Andrée Putman.

…in literature?

Depends on the seasons (of life).

Nota Bene

« The Adventures of Truth » – Painting and Philosophy: a story at the Maeght Foundation, Saint-Paul-de-Vence, from June 29 to November 11, 2013.

Exhibition catalog (Maeght Foundation/Grasset)